1. When Bulldozer כשדחפור

2. Blotted Out Hooligans חוליגנים מחוקים

3. Maminka מאמינקה

4. Hebron - Gola-Goola חברון - גולה-גלה

5. Stone אבן

6. Lady of Kinnereth הגברת מכנרת

7. Star כוכב

1997 - ORIEL 31, Newtown Wales, Feb.15 FIT TO STAND THE GAZE OF MILLIONS

room installation

Curators: Elaine Marshall, Michael Nixon

1997 - U.W.I.C Howard Gardens Gallery, Cardiff, Ap. FIT TO STAND THE GAZE OF MILLIONS, version 2 room installation

Curator: Walt Warrilow.

1997 - ORIEL 31, Newtown Wales, Feb.15 FIT TO STAND THE GAZE OF MILLIONS

room installation

Curators: Elaine Marshall, Michael Nixon

1997 - U.W.I.C Howard Gardens Gallery, Cardiff, Ap. FIT TO STAND THE GAZE OF MILLIONS, version 2 room installation

Curator: Walt Warrilow.

1997 - ORIEL 31, Newtown Wales, Feb.15 FIT TO STAND THE GAZE OF MILLIONS

room installation

Curators: Elaine Marshall, Michael Nixon

1997 - U.W.I.C Howard Gardens Gallery, Cardiff, Ap. FIT TO STAND THE GAZE OF MILLIONS, version 2 room installation

Curator: Walt Warrilow.

1997 - ORIEL 31, Newtown Wales, Feb.15 FIT TO STAND THE GAZE OF MILLIONS

room installation

Curators: Elaine Marshall, Michael Nixon

1997 - U.W.I.C Howard Gardens Gallery, Cardiff, Ap. FIT TO STAND THE GAZE OF MILLIONS, version 2 room installation

Curator: Walt Warrilow.

1997 - ORIEL 31, Newtown Wales, Feb.15 FIT TO STAND THE GAZE OF MILLIONS

room installation

Curators: Elaine Marshall, Michael Nixon

1997 - U.W.I.C Howard Gardens Gallery, Cardiff, Ap. FIT TO STAND THE GAZE OF MILLIONS, version 2 room installation

Curator: Walt Warrilow.

1997 - ORIEL 31, Newtown Wales, Feb.15 FIT TO STAND THE GAZE OF MILLIONS

room installation

Curators: Elaine Marshall, Michael Nixon

1997 - U.W.I.C Howard Gardens Gallery, Cardiff, Ap. FIT TO STAND THE GAZE OF MILLIONS, version 2 room installation

Curator: Walt Warrilow.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that the horse's tail is also used for making paintbrushes Avi Lubin, October 2017

Tamar Getter

THE ASIATIC COMPANY BUILDING 2003

Installation in two sites: Weizman Square, Holon, and The Mishkan Le'Omanut, Museum of Art, Ein Harod

The Asiatic Company Building 03

Installation in two sites: Weizman Square, Holon, and The Mishkan Le'Omanut, Museum of Art, Ein Harod

(Holon-Copenhagen – photography-painting)

Production:

The Israeli Center for Digital Art, Holon | within the exhibition "Rather Local," Weizman Square, Holon

Curators: Noa Zait, Galit Eilat

Gov Productions Ltd. in collaboration with Talui Ltd. under the auspices of Holon Municipality, The Society for Leisure and Entertainment (Holon), Ltd.;

Mishkan Le'Omanut, Museum of Art, Ein Harod

Curator: Galia Bar Or

Assistants: Valery Bolotin, Yura Gorelov, Yaniv Shapira, Ayala Oppenheimer

Photographs: Avraham Hay, Penny Yassour, Yoav Kosh (Geshem Communication)

Digital prints: Kobby Ran 89 Studio, Ramat Gan

Prints: Ram Bracha

The title The Asiatic Company refers to the building housing an oceanic trade business in Copenhagen. It is also the title of two oil paintings by Danish artist Vilhelm Hammershǿi, who depicted that harbor building twice in 1902: with its gates shut (146.5x140.5 cm), and with its gates open, a vessel seen behind it (158x166 cm).

Installation:

The Asiatic Company Building 03 was executed in two stages. In the first, the building and portrait paintings were installed as part of the Weizman Square Project in Holon; in the second, the paintings were photographed in their various locations in the square: Bank Massad, supermarket, tailor's shop, Benny Hair Styling, and ISSTA travel agency. The paintings and these new photographs formed the installation at the Mishkan Le'Omanut, Museum of Art, Ein Harod. The paintings and photographs enclose a whole whose separate units have no independent status.

Paintings: oil-tempera, applied with squeegee, sponge, and scraper, on wood

The installation space in Ein Harod:

The work's components were arranged according to a predetermined housing project-like plan, in six groups, each comprising four paintings and five photographs. The scheme of each group was as follows:

1. The Asiatic Company Building with gates closed (painting)

2. The Asiatic Company Building with gates open (painting)

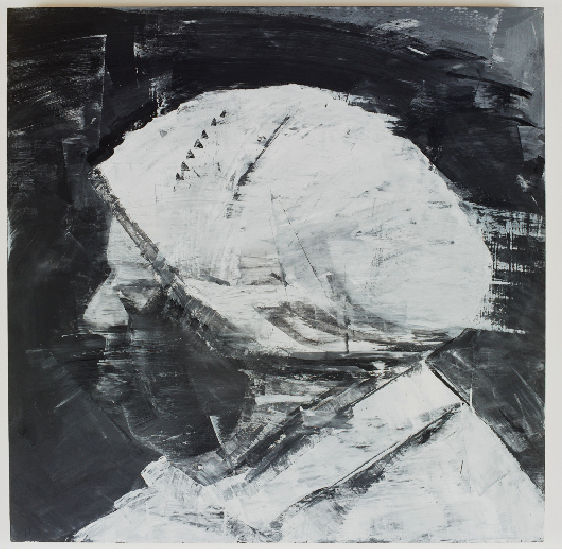

3. Portrait (painting)

4. Portrait (painting)

5. A series of 4 photographs

6. A single photograph of ascending stairs

Buildings:

12 marked renderings, via projection, of Hammershǿi's two paintings in gradually increasing scale from the original paintings. The enlargement results in an intensified perspective of the pictures set in the exhibition space.

The building dimensions in pairs on the walls in Ein Harod, from group 1 to 6

(right: The Asiatic Company Building with gates open; left: The Asiatic Company Building with gates closed):

1. 146.5x140.5 cm / 158x166 cm

2. 152.5x146.5 cm / 162x170 cm

3. 158.5x152.5 cm / 166x174 cm

4. 164.5x158.5 cm / 170x178 cm

5. 170.5x164.5 cm / 174x182 cm

6. 176.5x170.5 cm / 178x186 cm

Portraits:

12 paintings after photographs taken in Weizman Square, Holon, of local workers and passersby, the majority of them immigrants from FSU. Dimensions: 100x100 cm each.

The Photograph Quartets:

The photographic act addresses various aspects of optical flattening – fusion, linking, fastening, and a superimposed introduction of the building paintings, their exhibition spaces and the square, with its buildings, shops, and people. The 24 photographs, 51x57 cm each, comprise 6 series, each containing 4 photographs:

1. Classical schemes: Mast, Antigone, Fortuna, Villa

2. Facilities: Supermarket, Robert the Tailor, Benny the Hairdresser, ISSTA World Tour travel agency

3. Fusions: Milk, Cascade, Elongated Façade, Head-Car

4. The Palm Tree: Glass-blocks, Corner, Long Shadows, Palm Tree

5. Grafting: Waitress, Mecca, Boy, Lady with Hat

6. Bank Massad: Babushka, Shadowed Hammershǿi I, Bank Massad, Russian Girl

Ascending the Stairs:

A separate, deep-perspective series comprised of six photographs, 79.5x60.5 cm each, depicting climbing upstairs. Six different staircases, most of them photographed in South Tel Aviv

Assistant: Noa Zait; Prints: Ram Bracha

On the Building, the Painter, and the Square

The Asiatic Company Building (aka Philip de Lange's Palais) now serves the Protocol Department of the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs on Strandgade Street (the first street in Christianshavn Quarter), Copenhagen. Its first wing, the "Palais," was built in the late 18th century, in the golden period of trade between Denmark and the Far East, by architect and contractor Philip de Lange, as an office building for the Asiatic Company. The heavy and dignified façade facing the street is made of red brickwork in late Baroque style, with heavy pilasters emphasizing the middle part and the mansard roof. Some years later, a parallel building east of the 'Palais,' and a wall with vaulted gate to connect the two buildings, were erected. To preserve symmetry, the façade of the new building was made to match the façade of the "Palais," and was thus called the "Pendant." The building's interior and its rear section, facing the harbor, attest that it was planned and even served as a warehouse.

Vilhelm Hammershǿi (1864-1916) is a painter of late Romanticism and early modernism, who criticized Romanticism for its swift yielding to the culture of the spectacle, bowing to its quintessential passion for the shocking and deviant. His fear of art's deterioration into entertainment (which was increasing in his time), paired with his hatred for the iron stomach of the Bourgeoisie, which he perceived as a nondiscriminating stimulus grinder, shaped his critical approach toward the new modern tendencies; these tendencies he regarded as the direct followers of Romantic sensuality. He developed an unusual painterly mode, foreign to almost any type of stylistic or periodical classification, and as a critic, he introduced a unique model of conscious conservatism. Thus, while his paintings form a decisive negation of modernity, the offspring of Romanticism, appearing strange and archaic in comparison to the avant-garde manifestations of his time, Hammershǿi was indeed a downright conservative, a fanatic for pure and nonsentimental formalism, who cultivated a utopian dream of classical art, and at the same time (despite that utopianism or rather, because of it), he was also an ardent supporter of the avant-garde, and openly confronted the academic painters of his time, ostensibly his natural allies, whom he despised.

Hammershǿi's dread of modernity shares many similarities with that of Walter Benjamin. Like him, he predicted an entire process of total value collapse. Hence the unique ethics of The Asiatic Company Building: a rather technical painting, "uninteresting," of an office building with olden grandeur. From the other end of the 20th century, its mummified classicism elicits interest due to the particular accent – aesthetic but also inherently political – it conveys to our awareness of the familiar, of that which surrounds us and of the local.

The rectangle of Hammershǿi's painting is a locus of pure secularism, but the gaze invested in the negation of emotional drift bears an ascetic religious quality. The painting's inviting detachment interprets the pause before an object (building) in normative terms, further asking how an object should confront us. The ultra-quiet, reserved study invested in the building necessarily implies a thought about a desired man-to-man stand. It is something to work on and work for. This is Hammershǿi's significance – the man who painted mansions and shrines, sanctifying nothing. His painting transpires in a stoic stillness, embracing absolute certainty about a world which has no intention of allowing seriousness. His prosaic demand, factual brush, and the silent acknowledgment of sure failure arising from this painting, made me want to point at it via multiplication and repetition; the city square, and subsequently, the museum hall filled with numerous "Hammershǿis," was meant to address the work still needed here, in our intolerant Israeli culture.

Holon's Weizman Square was built in the late 1960s. In its modest internalization of the brutalist tradition in Israeli architecture, it sustains a tiny urban island of sanity and restraint, a different entity within the ugly, ostentatious urbanism gradually closing in on the cities and on life here, in dreadful keeping with the messianic drift.